Textile mills can be found throughout New England wherever the power of a river can be harnessed. From those as small as the Ten Mill River in southeastern Massachusetts to more substantial rivers such as the Blackstone River in Rhode Island, and the mighty Merrimack of Lowell, MA, water was diverted to turbines. Through gears, the power was transmitted to machinery... looms, spinners, carders. Managing the machinery were the hands and eyes of many, ensuring that threads don't tangle or snap, bobbins run out, shuttles go awry. Noisy, tedious work from sun-up to sundown. It all began when an Englishman named Samuel Slater (1768-1835) established the first successful water-powered textile mill on the Blackstone River in Pawtucket, RI in 1793. In history books he is credited as the Founder of the American Industrial Revolution. He was still alive when ancestors Louis Fournier and Zoël Turcotte were born on struggling farms in Québec in 1830, and Antoine Dargie was born of the same circumstances around 1820.

mill girls c.1867

In August of 1986, the Providence (RI) Sunday Journal ran several pages on the city of Woonsocket, the textile mills and the people who worked in them a half-century earlier. This is an excerpt of one of the articles written by Karen Lee Ziner, a Journal Staff writer. It follows the experiences of three young girls, teenagers actually...

The darker side of the mills can be seen in the exploitation of workers. At the same time as mills were being built, the same investors were building living quarters, long blocks of tenements, boarding houses, company stores. A worker could put in a 50-hour week and see little of his earnings in his pay envelope because the obligation of his rent and tally from the company store was taken out right up front. And what if the worker was an illiterate immigrant who didn't speak the language? And then there was child labor...

Organized labor fought early on to ban child labor, not only in textile mills, but all over the country, but it took 100 years to pass a meaningful bill. As early as 1832, New England unions condemned child labor. Then, in 1836, Massachusetts passed its first state child labor law which required children under 15 working in factories to attend school at least three months a year. In 1842, Massachustts limited children's workdays to 10 hours. The labor movement in 1876 urged a minimum age law that would ban the employment of children under the age of 14. Bit by bit and step by The National Child Labor Committee’s work to end child labor was combined with efforts to provide free, compulsory education for all children, and culminated in the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, which set federal standards for child labor. ...................................................................... Source for the data on child labor is the website: Child Labor Public Education Project Spinning room. Eventually, it got all sorted out, and when the heyday of the textile mills was finished early in the 20th century, New England was left with the memories of once-prosperous mills and a population of well over a million French-Canadians. A whirlwind in the late 19th century happened when that great flock of French-Canadians had to take flight and resettle where they could prosper.

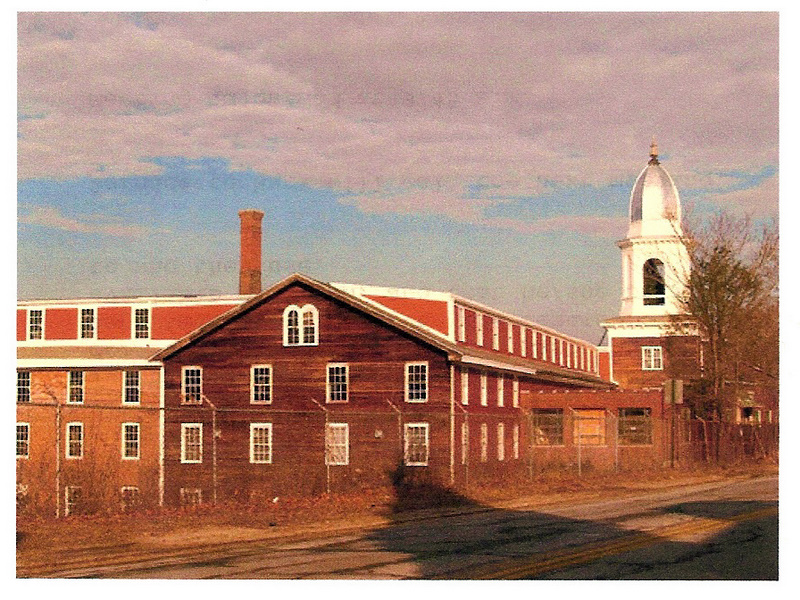

Recent photo of the Dodgeville Mill in Attleboro, MA

|

||

|

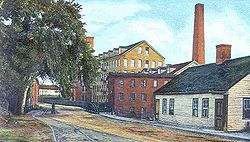

Assawaga Mill in Dayville (Killingly), CT as it was in 1909. |

|

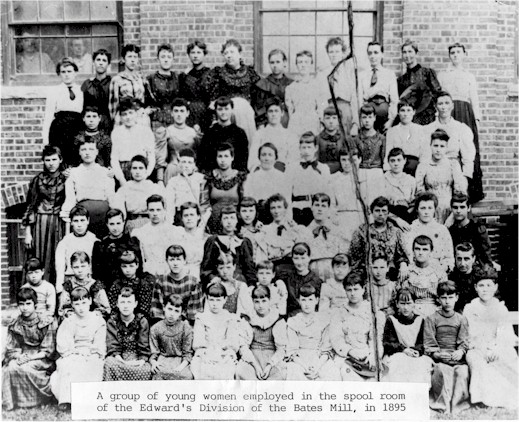

Some of the "young women" in the first two rows appear surprisingly young... ten or twelve, maybe.

Some of the "young women" in the first two rows appear surprisingly young... ten or twelve, maybe.