The Dodgeville Mill

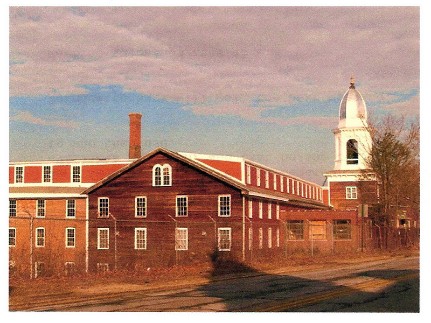

Photo of the Dodgeville Mill in Attleboro, MA, c. early 1900's.

Any story of a textile mill built in the early years of the 19th century must begin with a river. In the case of the Dodgeville Mill, it is the Ten Mile River. Now, the Ten Mile River is certainly not as dramatic as Rhode Island's Blackstone River or as mighty as the Connecticut River which slices New England in half, matter of fact, it is even misnamed because the Ten Mile River is actually twenty miles long. But this slow-running Massachusetts waterway had a potential for power, nonetheless, and that fact didn't go unnoticed by the entrepreneurs of the day.

In the year 1809, a group of six businessmen, among them Rhode Islanders Ebenezer Tyler of Pawtucket, and Nehemiah Dodge and Abner Daggett of Providence, selected a site along the Ten Mile River to establish a mill. Numbered among the first hundred cotton mills to operate in the United States, the infant company first conducted business under the firm name of the Attleborough Manufacturing Company, but was later changed to the Tyler Manufacturing Company in 1812. When Nehemiah Dodge and his son John C. Dodge bought out the other investors in 1822, the firm name changed to the N. and J. C. Dodge Company. Under the father and son partnership, the industry thrived for many years and from the young enterprise sprouted a thriving little community, typical of the small New England textile villages of that day.

The original building was three stories high with dimensions of 88x31. The B. B. & R. Knight Company later converted this structure, built along the lines of the Old Slater Mill in Pawtucket, into a machine shop.

Expansion of manufacturing facilities started in 1829 when the Dodges added 96 feet to make the building 184x31. At that time, 4000 spindles and 92 power looms employed 130 hands.

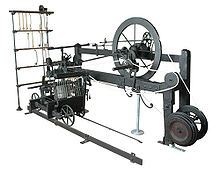

A mule-jenny used to spin thread.

In 1834, historian John Daggett wrote:

"It is the largest establishment of the kind in the town. The village, which is known as Dodgeville, has been recently very much improved under the superitendence of the present agent (J. C. Dodge). It contains a population of 260 persons, (all connected with the manufacturing establishment), one machine shop, one store, one blacksmith shop, four barns and 15 dwelling houses many of them new. It forms district 23 and has a new commodious and uncommonly well finished schoolhouse, where school is kept the greater part of the year."

The Dodge father and son partnership flourished for may years and the village grew steadily in keeping with the ever-growing business. The partnership was dissolved in 1840 when John Dodge purchased his father's interest in the concern. The younger Dodge then launched an expansion program. Several additions were made to the factory during the next ten years and the number of looms was icreased to 136. The firm suffered reverses in later years, however, and the property was finally sold at public auction in June 1854 to the Messrs. B. B. & R. Knight, owners of several mill properties in Rhode Island and Massachusetts villages including the Hebronville mill, whick they purchased in 1848. John C. Dodge, who was born in Providence in 1798, died in New York, Jan. 27, 1866, where he had moved his family.

When the Knights purchased the Dodge factory in 1854, they added another link in the chain which formed the vast Knight textile dynasty. Shortly after acquirimg the mill another brother, Stephen A. Knight, was admitted to the firm, becoming manager of both twin-village (Hebroville and Dodgeville) factories. In 1870, they incorporated with a nominal capital of $100,000 under the name of Hebron Manufacturing Company.

Producers of the famous Fruit of the Loom cloth, the Knights enlarged the mill to meet the increased demands of the market to 380x60, added another floor, making it four stories high, and built two spacious wings. Waterpower, which had served the old mill for years, was becoming inadequate and the steam engine was introduced to help step up production. In 1893, about 230 men and women were employed at the plant turning 22,000 spindles and operating 500 looms to consume 1,250,000 pounds of raw cotton and produced 2,500,000 yards of cloth annually.

were employed at the plant turning 22,000 spindles and operating 500 looms to consume 1,250,000 pounds of raw cotton and produced 2,500,000 yards of cloth annually.

New England industry was suffering from growing pains in the 1880's. Help was scarce and consequently there appeared upon the village scene, scores of welcome immigrants, a majority of them from Canada, but many from Ireland, England and Germany to form a thriving commuity. Attracted to the United States, French Canadians deserted their native provinces, particularly Quebec, where they worked in lumber camps or were farmers, in order to better their fortunes.

A large tract of land about half way between the villages of Hebronville and Dodgeville had been donated by the Knights for the purpose of erecting a Catholic church and establishing a cemetery. For many years Father Patrick McGee, who founded St. Stephen's on this land, lived in a small tenement, made the rounds of his parish afoot, was his own sexton in order to make financial ends meet, and coveyed the message of God in both English and French.

The Knight firm maintained the economic life of the village. They owned the greater part of the property in the commuity including 100 tenements, a large boarding house for itinerant workers with no family ties, a general store, farms, ice houses and numerous other buildings connected with the mill. Workers traded at the compay store where everything in the line of food, clothing, fuel, furniture and even jewelry and bicycles could be purchased. They also lived in company tenements and purchases and rents were deducted from weekly pay envelopes.

Among the men and women working at the Dodgeville Mill, and partaking of this village life at the end of the nineteenth century were many of my ancestors. People from the far-flung villages of Quebec who met and married, and forgot the promises made to themselves to return to Canada one day. Father McGee married my great-grandparents in St. Stephen's in 1885.

High and low levels were reached in the transportation systems during the Knight era. Railroads provided the only means of transportation until 1892 when the electric car made its first appearance, an event that was accompanied with great excitement. With the long hours of work in the mills, trips to the city were more a weekend event rather than an everyday occurrence. In pre-electric car days, villagers lived pretty much at home. Hourly train service to and from nearby cities was maintained, but the railroads suffered from trolley competition. Soon, schedules were dropped to two hour, three hour and finally to one stop a day. Freight depots and ticket offices were closed and the service was eventually abandoned entirely. The streetcar business boomed for nearly 25 years but was finally forced to bow to progress. Good roads and improved motor cars proved a combination that brought shopping centers nearer and nearer to the village and car lines were abadoned and busses pressed into service.

Twice the Dodgeville plant was seriously threatened by fire. The first blaze occurred in 1885 and the second in 1894. Both fires, oddly enough, started in the mule room on the third floor. But it wouldn't be fire that would herald the beginning of the end of this textile mill.

The Dodgeville mill and the Knight system of ownership continued for better than twenty more years until shortly before World War I, the company store was abandoned. Then, in the early 1920's came an announcement that struck the town like a thunderbolt--the mill was closing down. Official notices were posted on mill bulletin boards to the effect that the firm was to liquidate. Changes in modes of manufacture and also in the transportation field were blamed among other things as the principal reasons for the breakdown in the system that would throw nearly 500 workers out of employment.

Taken over by F. K. Rupprecht, dismantling operations soon got underway. While mill hands looked on in utter dismay, spinning frames, looms, twisters, slubbers, carders in fact all machinery from which they had earned a livelihood for years was reduced to junk umder the wreckers' hammers.

Credit for much, if not most, of this page must go to a Joe Pelletier, who in the late 1930's wrote an article for a local newspaper entitled: Dodgeville, Typical N. E. Mill Village, Has Been Supported by One Industry for Nearly 130 Years.

The Dodgeville mill continued on after the dismantling of late 1924 and became a bleachery, dyeing and finishing operation. My mother, Rhea Cameron Lizotte worked there a few years until 1938.

In 1984, the mill was shut down for the last time.

The Dodgeville Mill as it appears today.